Quiet Escalation: Balancing Pressure Points & Preventing Boiling Points

Graham Greene’s The Quiet American - A Perspective Lens on Intelligence Cycles and Escalation Spirals

Introduction

Graham Greene’s 1955 novel The Quiet American is one of his most personal, prescient and ultimately cynical works. Looking at the intrigues of post-WW2 Indochina, where Greene spent considerable time over the course of three years in the early 1950s. He was present to bear witness to France's last gasps of colonialism and America’s first forays into the folly of the Vietnam War. He paints a picture of a naive America and its acolytes not looking hard enough before they leap. Oblique involvement seemed to be the name of the game for the United States at that juncture, attempting to enjoin a nationalist “third force” into the fighting as a counterweight to the faded colonial ambitions of France and a contrary alternative to the dreaded communist-nationalist forces led by Ho Chi Minh. For a novel written in the mid 1950s to predict the disastrous entanglement the United States would come to have in Vietnam is a feat of near psychic foresight and goes to show the depth of Greene’s understanding of contemporary geopolitics.

Graham Greene’s connections with espionage began early on in his career and was in some ways the “family business”, with several of his siblings working for the intelligence services. In the mid 1930s Greene traveled to Liberia and Sierra Leone for a month-long traverse of the little explored area. His account of that trip, A Journey Without Maps, one he described himself as "absurd and reckless" and "a kind of Russian Roulette," represented his first view of the colonial world of what’s now referred to as the global south.(1) He then spent time in the late 1930s in Mexico, the setting for his masterpiece The Power and the Glory. A novel which told the story of anti-Catholic sentiments among Mexico’s revolutionary vanguard and the states of fallen grace of the “whiskey” priests confronting this threat during the Cristero War. From the same trip he produced a non-fiction traveler’s account known as The Lawless Road, where he let rip his unflattering sentiments towards the corrupt and dangerous land he found Mexico to be at that time.(2)

In 1941 with the outbreak of World War II Greene was recruited to work for MI6 by his sister Elizabeth, who along with other of the Greene siblings was working with the fledgling intelligence agency. He was assigned to Sierra Leone for the duration of the war and even worked under the infamous Kim Philby for a time, Greene would later go on to write the introduction to Philby’s memoir My Private War.(3) After resigning his role with MI6 in 1944 Greene wrote the screenplay for one of the best spy thrillers of all time, the Orson Welles directed masterpiece The Third Man. He would then end up in French Indochina right as things began to rapidly heat up there. Being in the right place at the most crucial junctures seemed to be a special knack Greene had throughout his career. His instincts for where the story would be and what the story actually was, are in hindsight nearly unrivaled among authors or correspondents of his day. He managed to enmesh and ingratiate himself with Papa Doc in Haiti and Fidel Castro’s rebels in Cuba later on in the 1950s, even aiding them by transporting supplies to their mountain redoubts in the last days of the revolutionary overthrow of the Batista regime. Acts that would lead to what must have been a thick file at Langley, one that surely only grew thicker through the years. Castro later gifted Greene a painting which hung in his home for decades, though the author did end up expressing doubts about the enigmatic communist leader in the end.(4)

The parallels between the novel The Quiet American and Greene’s own life are stark and instructive. His thinly veiled portrait of the British correspondent Thomas Fowler serves only as a cutout for Greene’s own harshly cynical worldview and a stand-in for the struggles of character and conscience that Greene himself wrestled with throughout his life. Greene, like Fowler, was married to a devout Catholic woman, but they lived in an estranged fashion for most of the duration of his life. Whereas Fowler was granted the clemency of a divorce in the end, Greene’s wife never consented to such an arrangement and the two stayed officially married until his death in 1991, though he lived with another woman for several decades. Greene, also just like Fowler, had an affair with a woman in his immediate social circle, an American married to a Brit businessman, this would be presumed to be the Anne mentioned by Fowler’s wife in her letters to him. Greene wrote of this incident directly in a novelized form in The End of the Affair which was published just a few years prior to The Quiet American.(5) I believe it was Paul Theroux who said that the worst thing that can happen to a family is for it to birth a novelist. Greene's open book nature and barely veiled fiction provide ample evidence for this notion. The closeness with which he hewed to reality actually led to him facing several libel suits during his career, including one involving Shirley Temple.

The openly transparent nature and harsh inward gaze Greene directed at his own personal life seemed to carry over to his opinions and observations of the various political machinations he came across during the course of his career. The clarity of his personal eviscerations regarding his own failings lends his critiques of others and their motivations a peculiar shine and grants him unique psychological insight. So much time spent peering into the recesses of his own dark soul likely helped him cast a proper light on the self deception and double-dealing intrigues of the wider world around him.

Pico Iyer says of The Quiet American, “The novel asks every one of us what we want from a foreign place, and what we are planning to do with it. It points out that innocence and idealism can claim as many lives as the opposite, fearful cynicism.”(6)

In an interesting aside, the 1958 film version of the novel directed by Joseph Mankiewicz(7) , flipped the script of the plot, taking away the agency and downplaying the duplicity of Pyle and making Fowler out to be a patsy of the communists. Letting himself be duped into betraying the do-gooder American, only there to help a helpless people. Audie Murphy played Pyle in this adaption, a quiet American no doubt, but a far from naive one given his violent war service, so the casting just feels off. The most fascinating part is that it was filmed in Saigon in 1958. That window between when Greene predicts the doom that will befall American involvement with his novel and the onset of the regrettable actions that turn into the catastrophe of the Vietnam War, or as the Vietnamese, perhaps more appropriately refer to it, the American War. There are rumors that have always swirled around the film suggesting that it was arranged and stage managed by the CIA and was in fact an elaborate piece of noir tinged propaganda.(8) Eerily similar to the rumors surrounding “Winds of Change”, this makes one wonder and hope that just maybe Patrick Radden Keefe is casting about for another podcast idea.

The American Pyle and Fowler’s Brit in some ways represent the same man just caught at different points of the spectrum in the arc of experience we all go through. I first read this novel 10-12 years ago, just before my own initial excursions to Vietnam. At that time I recall feeling a strong connection to Pyle and his raw exuberance, with only a whiff of Fowler’s cynicism befouling my worldview. Fast forward a decade and the novel hits differently for sure. I can now see the story from many angles and identify a lot more with the correspondent Fowler, as someone who has seen too much and gone too far to turn back.

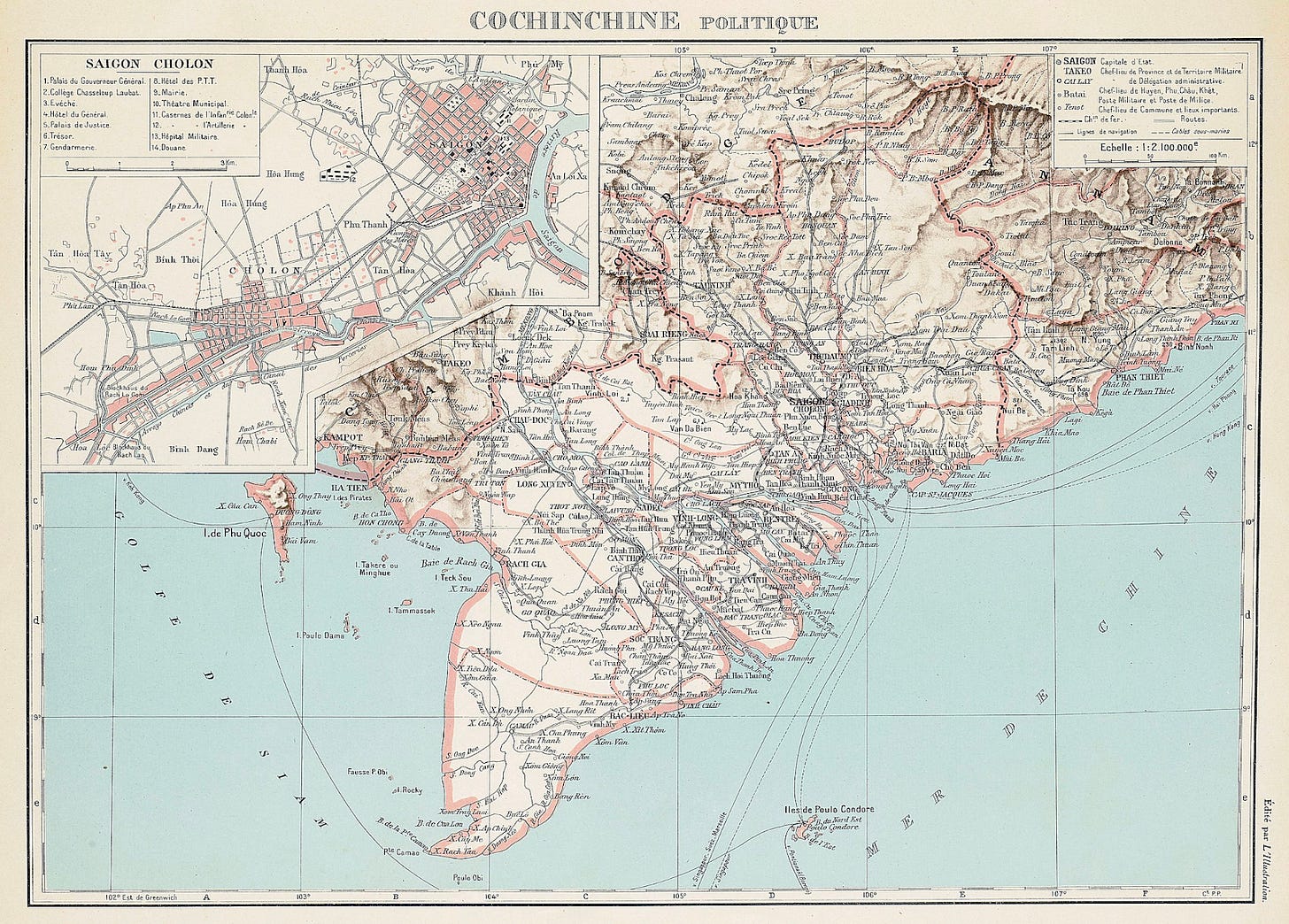

The Silent Cycle

The novel thrusts the reader into the midst of a long simmering conflict and the immensely convoluted milieu that was mid 20th century South Vietnam. It really all began decades earlier when the French arrived in Indochina en masse. After the benevolence of the Jesuits who had set up shop in Vietnam far back in the 1700s, the French intrusion became another in the long line of wannabe suzerains in the region. Seizing Saigon in 1859 the French went on to gain control of most of southern Vietnam. This was formerly the dominion of the Champa Kingdom, an area the French came to call Cochinchine. Control of various regions was always nominal and outside the major cities jurisdiction was perfunctory at best. The jungle dangers of the night that came to the fore in the novel showed only the most armed and stoutly armored had a fighting chance.(13)

Prior to the vogue and vague theories of a “third force”, the OSS had actually backed Ho Chi Minh and his Viet Minh rebels in their fight against the Japanese, back in the all for one days of WW2.(9) The Cao Dai referred to in the novel, with their flamboyant blend of colorful religions, pagan idolatry and modern philosophy, were a real group who exist to this day. The mysterious General Thé was a real character too, it was this General who the CIA’s Edward Lansdale tapped in 1954 to run an opposition force in the south to counter the communists in the north.(10) Some have even insinuated Lansdale was the basis for Pyle but it’s sure that Greene knew of the CIA’s curious activities long before Lansdale came on the scene and the novel was mostly completed before Lansdale made his appearance.

Michael Caine who was a friend of Greene’s later in his life told a story of him being bemused but hardened in his cynicism by an event where a US diplomat’s car crashed and explosives were found in the trunk, but it was quickly swept under the rug by authorities and the press.(11) For the US intelligence community the ties that bind were already being forged early on in Vietnam and it’s remarkable that Greene not only picked up on these threads but wove them into the tapestry that served as a backdrop to his novel.(12) A book that is as much about crippling Catholicism, mid-life crises, and bad decisions under strained circumstances, as it is about spycraft or Vietnam. The drama of the dark arts of the world of spies, opium dens, and best laid plans just brings form and adds luster to the personal story being told.

The first stage of the intelligence cycle is identifying the threat. In the case of Vietnam in the 1950s the threats were anomalous and seemingly multiplying by the day. For the United States these threats were manifest in the idea of the “Domino Theory” and the global threat posed by communism. Having witnessed the events in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe and then China, the leadership in the West’s intelligence agencies at the time surely saw this threat as existential and ongoing. Pyle was sent there by the US to ply the back channels of possibility, to hopefully stop Vietnam from succumbing to the red menace of the Viet Minh. Fowler for his part came to identify the main threats being faced as coming from the duplicitous American. The terrorism being pushed as a strategy to destabilize Saigon and clear the deck of foreign involvement was too violent and too misdirected for Fowler to just ignore. Add to that the threat Pyle posed personally to the comfortable life Fowler had arranged for himself and his ultimate betrayal is hardly a surprise.

Collection is the next stage in the cycle, Pyle seemed to be utilizing Fowler as a source but in the end Fowler’s investigative instincts and prowess in navigating the intrigues of Saigon led him to harsh conclusions and impulsive action. Fowler let himself be flipped by the communists and the Chinese agents working on their behalf. The evidence he was shown was real but the manipulation of his emotions and divided loyalties by the Chinese was masterful nonetheless. Yet, still he had regrets and his shame over his actions would have always left the window open for leveraging by the Western powers to provide penance in the form of counterintelligence. Fowler came to believe in the dangerous naivete and strong but misguided moral fiber of the wayward American agent. He became disgusted at the motivations, beliefs and consequences of American involvement in an already lost French colonial cause. Fowler’s love for Phuong and the competition posed by Pyle did not help clear the opaque fog of war that they all stumbled around in half blind.

Processing and analysis is the next stage of the intelligence cycle and this is a lot of what the novel is about. The insight provided into Fowler’s motivations and thought process as he wrestles with the facts that come into his purview does well to show the demanding and discombobulating nature of crafting a narrative from bits and bobs of information during such a fraught time period. The condensed and often overlapping temporal movement of events, added to the complexity of judging context properly with disputed facts, this forces any intelligence agent to be ever vigilant of potential blindspots.

Misconstruing an event in such a charged atmosphere as a war zone can quickly create a situation where things spiral in an uncontrolled way. Guarding against this within the broader context of French Indochina was never going to be simple or straightforward. Fowler does his best to reconcile his own moral compass, with the ruthless world of the realists and the necessity of intelligence operations, but in the end his betrayal of Pyle was inevitable given the lens through which he had come to view the world of 1950s Vietnam. Sitting on the rooftop watching the US unload armaments while having a cocktail and wrestling with his own inner demons was a running theme in the book. The US eventually shipped around $4 billion worth of arms and supplies to the South Vietnamese during this period.(13) The rest as we know is history.

Disseminating and acting upon intelligence is the final step in the cycle and is the stage that represents the third act of the novel. Fowler missed a key component of the story and had a huge blindspot regarding Pyle for a large chunk of the book. Phuong tells Fowler about the “plastique” that Pyle has been importing on page 86. Unfortunately Fowler misinterprets this essential clue and assumes she is merely saying plastic. Which given the French pronunciation does make sense, but anyone with even limited military knowledge recognizes “plastique” to be a reference to plastic explosives. The use case for plastic is a far different one than that of plastique, and this mistake leaves Fowler in the dark much longer than you’d expect given his incisive eye regarding all else. By the time Fowler came around to the realization of the full extent of Pyle’s involvement, his desperation to keep Phuong and the trauma of seeing the direct and violent effects of Pyle’s plastique “toys” in the square leads him to his ultimate decision. The scene with Pyle in the apartment when he reads the book at the window to alert the agents is the culmination of all the Fowler has seen and his disgust mingled with fear pushes him towards the choice. He later regrets it as not only unsporting, but quite possibly unjust as well. It illustrates the importance of an intelligence apparatus to analyze and reinterpret what has been gathered, since agents in the field are often too close to their own narrative to see possible alternatives or recognize ulterior motives.

Chutes and Ladders

The escalation ladder theory was first put forth in the 1960s by Herman Kahn of the Hoover Institute. His step by step action guide spelled out precisely how to increasingly ratchet up tensions, what was known then as the preferred “Third Option”. Moving up from mild diplomatic pressure all the way to nuclear war. It is a harrowing set of rungs to find oneself negotiating. Presumably diplomatic tacticians ascending this ladder don’t kick the rungs out as they go; it can be an effective guide for manipulating your adversary through an array of interesting means.

America’s meddling in Vietnam seems in hindsight an obvious outgrowth of the ‘all or nothing’ containment strategy that came to define Cold War international relations early on. The existential threat was encroaching Communism and the only way to nip it in the bud was to stomp out its spread early and everywhere. That became the moral imperative that defined the US mission as it saw it through a succession of presidential administrations both Democrat and Republican. The era of this novel would have been Eisenhower’s, so the general seemingly understood the value of good intelligence.

The 55 rung escalation ladder begins down in the realm of what amounts to no more than routine and unsurprising operations. From benign propaganda, to CIA advice, to economic counsel, one assumes to our benefit as much as Vietnam’s. This seems to be where Fowler first suspects Pyle to be lurking. A nuisance of a fly rather than a tiger of a true threat. The second threshold known as “Modest Intrusions” is where things begin to heat up, with false propaganda and funding of adversarial forces within the country. A covert rather than overt influence, it is hoped at this point.

Threshold three, rungs 13 through 36, the so-called “High Risk Operations” are where things start to get a bit spicy, with plausibly deniable covert influence potentially tipping over into overt involvement and with blatantly malevolent intentions. These measures run the gamut from increased propaganda and political involvement, then move pretty quickly to providing munitions to allies and neutral actors engaged in the action. From there the pressure mounts into full fledged support for alternative political players and black propaganda. Then vaults up to providing heavy weaponry, attempts to cite rebellion with propaganda, and direct involvement by CIA officers in paramilitary activity. This is when the gloves start to come off and the US hits the in for a penny in for a pound point of no return. The book predates Kahn’s ladder but the playbook seemed to already be in place by the point of the events of the novel. The French general during the press conference even gives the game away essentially, when he begs for helicopters from the Americans in front of the entire press corp. Although anyone who happened to frequent the rooftop bars that were the haunt of Greene were well aware of the American involvement and could even guess at the approximate tonnage of skin we had in the game at that point based merely on astute observation.

Greene came up during the tail end of Britain's colonial legacy, a time when the bitterness of sunk costs and misplaced assumptions had pulled the wool from the eyes of the most Victorian era colonialist. The idea that France’s cause was a lost one and the American’s a blundering one, seemed all too obvious to the cynical and analytical Greene. If only the US at the time had internalized some of that repentant grief of colonialism, rather than exclusively the triumphant exceptionalism of post WW2, maybe we’d have saved face and an immense amount of suffering from our blunders and unrealistic assumptions. In the book this plays out overlaid with the psychology of a panorama of characters trying to do what they see as their best in impossible circumstances. Pyle may be full of gung-ho optimism to mix it up and make good, but until the bombing in the square he doesn’t seem to take seriously his potentially pivotal role in the course of events. Even still he blunders forward heedless of the damage being wrought and oblivious to the danger beginning to surround him.

Threshold four is where the rubber meets the road, actions become direct, plausible deniability is lessened or eliminated entirely and there is likely no going back once this Rubicon has been crossed. Whenever ratcheting up tensions it’s important to remember that beyond a certain point reeling it back in becomes nigh on impossible and the escalation spiral hits a doom induced feedback loop. Tierney and Johnson in their article, “The Rubicon Theory of War: How the Path to Conflict Reaches the Point of No Return” discuss how the way to war is often meandering, but at a certain point the die is cast and the fates are settled.(14) Avoiding the inevitability of this path is critical when considering climbing the ladder of escalation. If both sides come to perceive conflict to be inevitable, then even in a case where it could have been avoided it won’t be. Walzer in looking at the justifications surrounding ‘just war' mentions how diplomacy as an avenue must always be kept open even if other routes are simultaneously being explored. And it was Clausewitz who stated that war is merely politics by other means.

Pyle perhaps saw his role as one that would eventually be vindicated by circumstances and it is the readers, with the benefit of hindsight, that can see how tragically naive this conceit was. The desire to help the Vietnamese was virtuous enough but the methods attempted were unfortunately far off the mark. Fowler for his part hopes to be able to de-escalate by publishing harsh truths and throwing around cynical hot takes. His own naivete allows him to misconstrue Pyle’s grander ambitions long enough to be truly shocked by the revelations of his actions. Would Fowler have betrayed Pyle without Phoung as part of the love triangle? One can wonder how the story between the two men might have played out had a woman not come between them. For Fowler his disgust with the actions of the Americans flowed through a prism of his own self loathing and Catholic guilt. Complicating his decision making and opening him up to the influence of his Chinese sources. Had Fowler’s Indian assistant visited the Chinese warehouse and seen the molds, maybe his filtering of the information would have led to different decisions. It’s also quite possible that Pyle was always in over his head and nothing Fowler did or didn’t do would have altered his and America’s ultimate fate.

By embarking on the path of clandestine escalation the US in 1950s Vietnam was haphazardly setting itself up for failure. Colonialism was fading fast and the vacuum it left was real. So the idea that communism could possibly march unchecked through the global south wasn’t so far-fetched. The problems arose within the execution stage of the cycle. Escalation of this sort must always be done with an eye towards an exit strategy. Starting wars is easy, extricating oneself from conflict once engaged is not. It behooves policy makers, politicians, intelligence officials and military leadership to all consider very carefully every rung up the escalation ladder they climb.

Finding oneself high on a ladder without the proper rungs for retreat is a dangerous place to end up. By removing the rungs as you climb there is then no exit strategy, and the only way ahead is further escalation. Elbridge Colby and Yashar Parsie have written recently on these exact issues in relation to the US-China-Taiwan issue.(15) They put forth a concept of “integrated deterrence” that involves outright denial in the space and adding the imposition of costs to make entry into that space unacceptably high for decision makers. Deterrence is usually accomplished by either punishment or denial. Punishment can too often end up in a retaliatory spiral of punch and counterpunch and also an economically devastating cycle of sanctions and tariffs. Denial can work to dissuade certain behaviors but decoupling, derisking, and reshoring are costly and not always effective, overly resilient supply chains can also be redundant and inefficient ones, thus weakening their ultimate effect. Even with the lessons learned from Vietnam and the 50 years of the Cold War, the thicket of intelligence gathering is still one in which it is easy to lose your way. Before even beginning the ascent up the escalation ladder the most important aspects of the planning need to be identifying a theory of victory and having an exit strategy for de-escalation. Deterrence can disintegrate as a strategy without clearly defined guardrails and off-ramps.

Conclusion

The remarkable life of Graham Greene was one that not only mirrored, but somehow even managed to outdo that of the protagonist’s he wrote about. Living in the smoke filled rooms, navigating the funhouse distortions in reality, and treading in the waters of intrigue, innuendo and intelligence, was just normal day to day existence for him apparently. Always being at the right place at the right time, with the right connections were his calling cards. It no doubt helped having, what is assumed to be, a lifelong acquaintance with the MI6 and who knows what other intelligence services.(16) Greene managed to carve out a career somewhere in the murky liminal space between making art and active intelligence gathering.

Moral ambiguities became Greene’s bread and butter and the ethical dilemmas inherent to intelligence work the fodder for his plots. Masterfully weaving fact with fiction Greene’s novels managed to tease out the world of espionage in a unique and insightful way. The Quiet American helps expose the shortcomings of the intelligence collection cycle and the consequences of ascending the escalation ladder too quickly, especially when in the maw of unchecked idealism cloaked in moral imperatives. It’s far too easy to cast aside better judgment and see any and all threats in the same light as existential ones. When righteous idealism arrives with a moral imperative in tow and meets up with what is perceived as an existential threat the blowback and collateral damage can’t be far behind.(17) It’s why I personally worry a bit about the narrative emerging in the West regarding China and Taiwan, but I digress.

The Quiet American does more than just condemn the moral failings of its main characters Fowler and Pyle. It points towards the dangers that arrive when the Pandora’s box of misguided good intentions is opened. The novel shows the necessity of proper intelligence gathering but does so by showing what can happen when it all goes sideways. Cherry picking pieces of the picture and crafting a narrative that best serves personal beliefs or top down notions of half-baked policy can rapidly backfire. The cycle of intelligence is never separate from the Machiavellian machinations of political manipulation, errant agendas, and flatout ignorance.

The novel also shows the careful consideration that must be given to the consequences of escalation even that of the quiet and clandestine kind. Seemingly small actions today can cascade into more monumental consequences months or even years down the line. If the Pyle in the novel were aware of the next stages of US involvement in Vietnam and how they’d ultimately culminate, perhaps he’d hold York’s ideas up for harsher interrogation. Maintaining a meta-awareness of one’s own potential naivete despite best laid plans and the purest of intentions is therefore key. It was in these moments of moral quandary that Greene seemed to excel and become a clear eyed chronicler of the complicated plots playing out all around.

Sources:

“Journey Without Maps.” Wikipedia, 22 Sept. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journey_Without_Maps.

“The Lawless Roads.” Wikipedia, 12 June 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lawless_Roads.

“Graham Greene.” Wikipedia, 4 Nov. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graham_Greene.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Iyer, Pico. “The Disquieting Resonance of ‘The Quiet American.’” NPR, 21 Apr. 2008, www.npr.org/2008/04/21/89542461/the-disquieting-resonance-of-the-quiet-american.

“Joseph L. Mankiewicz.” Wikipedia, 5 Sept. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_L._Mankiewicz.

Erickson, Glenn. “The Quiet American (1958).” Trailers From Hell, 26 Aug. 2020, https://trailersfromhell.com/the-quiet-american-1958/#google_vignette

PeriscopeFilm. “FRENCH INVOLVEMENT IN VIETNAM and DIEN BIEN PHU 72662.” YouTube, 21 May 2015, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XWY9KbIXpdI.

“Trình Minh Thế.” Wikipedia, 30 Aug. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tr%C3%ACnh_Minh_Th%E1%BA%BF

“Michael Caine on ‘the Quiet American’ (2003).” YouTube, 17 Mar. 2019, www.youtube.com/watch?v=aVs8dDJeEOc.

Real Time History. “Indochina 1946: The Forgotten Start of the Vietnam War (4K Documentary).” YouTube, 15 Sept. 2023, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XA8mpE14FeA.

Goscha, C. (2016) Vietnam: A New History. Basic Books, New York.

D. D. P. Johnson and Dominic Tierney. (2011). "The Rubicon Theory Of War: How The Path To Conflict Reaches The Point Of No Return". International Security. Volume 36, Issue 1. 7-40. https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-poli-sci/19

Colby, and Parsie. “Building a Strategy for Escalation and War Termination.” The Marathon Initiative, Nov. 2022. https://themarathoninitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/TMI-Building-a-Strategy-for-Escalation-and-War-Termination-FINAL-1.pdf

“Graham Greene the Spy, With Christopher Hull.” Apple Podcasts, 12 July 2019,

Mazarr, Michael J. Leap of Faith: Hubris, Negligence, and America’s Greatest Foreign Policy Tragedy. PublicAffairs, 2019.